Large numbers of people claim they’ve had some form of outlandish, transforming experience that defies both common sense and the laws of science. Some of these experiences are wonderful and visionary while others are horrific. Some people report picking up terrifying alien messages from blank TV screens. Others have unscrambled the voices of the dead from the static hiss of untuned radio sets. Some have parted company from their own flesh and stared down from mid-air at their own seemingly lifeless bodies. Others have communed with other minds via telepathy or seen objects hurled through the air by the power of thought alone.

All these scenarios inform the remarkable art of Susan Hiller, subject of a major Tate Britain exhibition that opens a week on Tuesday. Over a career spanning more than 40 years, this US-born, UK-resident artist has crafted images, objects, installations, audio, video and web projects, often discovering new artistic applications for new media. She is also celebrated as a writer, speaker, teacher and curator who has inspired generations of younger artists and critics – not least by opening their eyes to the value of such apparently unpromising material as the stories above.

From a rationalist viewpoint, such tales result either from nervous systems going on the blink or the survival of superstitious twaddle, or both. For the credulous, they prove that the planet really is secretly awash with demonic forces, disembodied spirits and little green men. Hiller’s work steers hard away from this dull stalemate. Researching exhaustively, gathering often vast quantities of data and recycling it in humorous, compelling new ways, she asks viewers to reconsider, to notice its variety, oddness and beauty. With its potential unleashed, she suggests, this supposedly generic, trivial or banal stuff builds into a powerful “argument for the primacy of the poetic imagination”. Take her audio installation Witness (2000). First made for Artangel and shown in an abandoned London chapel, this subtle, insidious work has travelled around the world. At the Tate it will draw still more viewers into its web of stories.

In a darkened room, a cloud of electronic droplets – dozens of tiny, opalescent speakers – hang from the ceiling on fine wires. As viewers wander about, they pick up the sound of individual voices speaking many languages. Each one recounts an extraterrestrial encounter. The babel of voices rises and falls; a single voice dominates then fades away. The witnesses are doctors, teachers, pilots, hikers, farmers, drivers, parents, children. The accounts, mainly found online, are voiced by a multilingual team of collaborators recruited by Hiller. They are by turns thrilling, absurd, lyrical, sad, or even strangely offhand, and spiked with piquant details. “This was a UFO fair dinkum!”; “My wife and I and our grandson, along with the bank manager, saw an object . . .”; “Two beings came to the window . . . Their conveyance was like the northern lights”; “I was exonerated and reinstated in the military academy . . . but I know I will never be accepted as normal again . . .” It’s a beautifully judged piece, luring visitors into its kaleidoscope of peculiar narratives but not expecting them to check in their critical faculties at the gallery entrance.

Hiller’s convictions about art and her decision to become an artist were influenced by her study of social science. Born in 1940 and raised in Florida, she embarked in her 20s on research in anthropology, but came to see the anthropologist’s “equal-but-different” participant-observer role (in which researchers rubbed shoulders with their subjects, yet claimed that the data they gathered was scientifically “objective”) as a sham. Art, she felt, would allow her to make work without any false claim to objectivity – she wanted to be free to live “inside all my activities”.

She also held that the best art was untrammelled by theories: in Gertrude Stein’s words, it was “made as it was made”. It’s a view she still advocates. “Not editing out and not forcing strange juxtapositions and unanswered questions to conform to theory is an aspect of my style, almost a signature,” she said in 1998. And a more recent comment hints that she sees not just a difference but a spark of opposition in the relations of art and science. “Artists’ research disturbs the kind of research that scientists do,” she noted in a talk with the critic Jörg Heiser last year.

By the early 1970s Hiller had moved to London, where she still lives, and was setting out the terms of her mature art practice. It was a kind of curatorship: a drawing-together of new works from pre-existing artefacts, images, histories and legends gleaned from the long grass of global culture. Her search for the curious, the overlooked and the intellectually discredited is, however, driven by political and ethical as well as aesthetic motives. To give significance to the apparently “meaningless, the banal, the unknown, even the weird and ridiculous” is to change the cultural balance of power – to recognise ideas and experiences that are scorned or stifled by mainstream culture and “normal life”. From this principle to the 1970s feminist practice of “consciousness raising” – acknowledging and articulating the repressed aspects of women’s lives – clearly isn’t a long stretch, and Hiller has always stressed her work’s feminist tendency.

Yet its cultural-political roots reach even further back, to the tactics and ideals of revolutionary surrealism, itself a movement widely disparaged by the modern art mainstream when Hiller was starting out. Like the surrealists she is fascinated by dreams, and in some early pieces she invited friends to work with her on a series of studies of their dream contents. The Tate show includes Dream Mapping (1974): diaries and maps recording dreams that came to the group while sleeping al fresco in the Wiltshire countryside over three midsummer nights. Borrowing a phrase from Magritte, this was a definite case of reckless sleeping, for all were lying in “fairy rings” formed by scotch bonnet mushrooms. These are held to be perilous gateways to the spirit world. Those who trespass into them may end up (among other bad things) in permanent thrall to their fantasies. It’s all supposed to be “intensely serious and very funny”.

Despite Dream Mapping‘s seemingly eccentric focus on fantasies and fables, it has an underlying link with the “official” early 1970s avant-garde, and in particular with the stripped-down, programme-driven, “anti-aesthetic” works of conceptualists such as American artist Joseph Kosuth or the British group Art & Language. Hiller, too, is a kind of conceptualist; she makes definite but subversive use of the movement’s methods. Many Hiller works, Dream Mapping included, set up task-like schemes and follow them strictly, presenting the results in a cool, systematic manner. At the same time, they license the visionary and voluptuous forces in art that conceptualism strove to suppress.

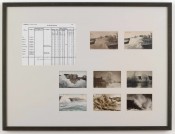

The vast project Dedicated to the Unknown Artists (1972-present) does just that. The task was to collect multiple examples of a genre of postcard. The results were logged. Details such as location, format, colour and the card’s written message were recorded, and the data was then displayed on a grid. All of which sounds pretty dry; but the sober process forms a brilliant foil for the fabulous antique postcards themselves. They show images of “Rough Seas”: giant waves cresting over cliffs and beaches, bombarding esplanades, grand hotels and piers and swamping heavily-clad early-20th-century daytrippers in clouds of spume. Some images are thrilling, some lovely, some ridiculous, some a mix of all three, and some are faked – enhanced with colour tinting and painted-on tsunamis. The cards and their banal, odd or touching messages emerge as wonderful. They are traditional landscape paintings in miniature: tiny echoes of the grand sublime tradition made by “unknown artists” and invested in by friends and relatives. They are also slim cracks in the polite surface of everyday life, hints of desires for the excessive, the unruly and the fantastic.

At the Tate, the “unknown artists” bask in the limelight once again in the most extensive presentation of Hiller’s work to date. There is recent work, much of it focusing on the internet as a hunting ground (plus, at the Timothy Taylor gallery in London’s west end, a further helping of new works, including a tribute to kindred spirit Stein). And many of her most famous projects are on view. Belshazzar’s Feast (1983-4) is an installation resembling a sitting room. Inside, viewers can relax on sofas and watch an old-fashioned TV screening Hiller’s video of the same name, a landmark work that was first broadcast late at night on Channel 4. It shows a flickering fire and its soundtrack includes eerie ritualistic singing and a whispering voice reading newspaper reports of alien messages broadcast on domestic TVs after closedown. The television is recast as a hearth or campfire: a place where the imagination may be set loose and fantasies incubated. Fittingly, the piece sits at the heart of the show.

There’s also From the Freud Museum (1991-1997), 50 cardboard archive boxes containing a trove of enigmatic small objects, images and texts: toys, herbs, maps, pottery shards, souvenirs, fakes, phials of holy water. Originating from Hiller’s 1994 residency at London’s Freud Museum, these microcosmic museums-within-a-museum are a kind of free association with physical stuff: reflections on museums, psychoanalysis, Freud’s life and Freudian lore.

There’s also a rare treat: a reconstruction of the startling An Entertainment (1990-91). A four-screen video installation, this was made for and first shown in the celebrated not-for-profit space Matt’s Gallery. It’s edited from footage from a traditional Punch and Judy show. Projections paint the gallery walls with images of the Punch family, Death, Devil and Hangman, grown monstrously large. They loom over viewers and dodge about the room, accompanied by shrieks, distorted voices, odd fragments of academic-sounding commentary and curious moralistic pronouncements. The impact of An Entertainment is visceral and disturbing. It shows how some of the “entertainments” we offer children fuse play and pleasure with fear and violence, without adding any comforting moral judgment.

And, technically, it’s brilliant – an achievement rendered doubly impressive when one registers that, in 1990, Hiller was not just making an immersive video installation but inventing the genre from scratch.

The Tate’s exhibition will bring many aspects of Hiller’s artistry into focus: the diversity and depth of her interests, her art’s vitality and humour, and her willingness to let it question and disturb rather than soothe and reassure. But, in this practice dedicated to the re-evaluation of the devalued, it may well be its commitment to the present that moves visitors most. Hiller’s work has faith in now – in new cultural stuff, new techniques and new media – and in the power of tracing connections between the cultural galaxies of the present and long, indeed ancient, traditions and customs of art.

Susan Hiller showed at Tate Britain, London, UK between February 1 – May 15, 2011. Susan Hiller, An Ongoing Investigation was on show at Timothy Taylor Gallery, London between February 3 – March 5 2011

Copyright Rachel Withers and Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies.