By now in Venice, the sometimes poor but usually tired and huddled masses of art professionals who attended the preview days of the city’s biennale will be long gone. The works they queued to see (for example, Pipilotti Rist’s hit Homo Sapiens Sapiens, a lush video work that paints the Chiesa di San Stae’s vaulted ceiling with images of naked nymphs and rainbow-coloured plant life, or Annette Messager’s loopy, Lion d’Or-winning, soft-sculptural automata in the French Pavilion) will now be open to the general public. The galleries will be near empty and ordinary visitors will able to view the works in conditions one imagines the artists would themselves prefer.

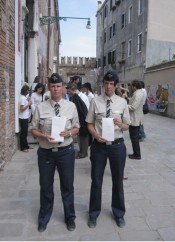

The big irony of the biennale preview is that it is the worst possible time to look at the art, as an unofficial performance at this year’s opening underlined. The Pilots, two fresh-faced Swedes, patrolled the entrance to the Arsenale shows in uniform, distributing paper “art sickness” bags and pastiching a flight attendant’s security drill. If art sickness struck, they instructed, sufferers should place the bags over nose and mouth and leave by the nearest exit.

Yet attending the previews remains a necessary ordeal if you need to stay on-message in the contemporary art world: it is a chance to network, and to see performers in action – be they guerrilla acts such as the Pilots or official stars such as John Bock, the German artist whose calculatedly nutty, chaotic “performance lecture” was staged for previewers’ eyes only.

The preview days also allow the art world to feed what has become an obsession: worrying about biennales. Well over a hundred exist and more are looming. Moscow’s first biennale opened in January; Singapore launches its very own next year. Alongside this, soul-searching symposia and panel discussions are now almost obligatory. Hands are wrung over a now predictable list of biennale-related anxieties: their problematic function as giant art-market showcases, their lack of relevance to their host communities, their usefulness for dodgy governments as cultural window-dressing, their tendency to reproduce the worst aspects of globalisation, their false utopianism, and so on.

Documenta (a huge art show staged every five years in the German town of Kassel) was prefaced last time around (in 2002) by a prestigious series of “platforms” focused on the event’s role in contemporary art. Venice is at it, too: Robert Storr, curator of the 2007 biennale, plans a symposium (next December) at which “leading experts” will analyse the causes of the art world’s galloping attack of Venice-inspired blockbusters. One might waspishly suggest that biennale discussants now face a question doubled: how to radicalise their approach to debating how they are going to radicalise their approach to staging biennial shows.

Venice 2005′s press days exhibited two sharply contrasting styles of biennale-bothering, in the shape of two early-morning series of talks – an arrangement that ensured both food for thought and two free breakfasts in quick succession.

“Agendas 2005: neighbours in dialogue”, co-ordinated by a collection of art schools in the UK and others, featured speakers from places with complex relations to the western mainstream of contemporary art: Beirut, Tehran, Cairo, Palestine, Belgrade, Tel Aviv, Derry. Both Gilane Tawadros, a participant in 2002′s Documenta 11, and this year’s Istanbul Biennale co-curator Charles Esche characterised Venice as almost a dinosaur: less than candid about its political and economic agendas, conservative in its curatorship, and the site of a forced, unequal encounter between artists from global centres and those from disenfranchised peripheries. “I’m close to giving up on Venice,” declared Esche. Venice’s curators should risk staging difficult, uncomfortable shows, challenged Tawadros. Her views were echoed by the curator of the Sydney Biennale 2006, Charles Merewether. His tip for Storr: avoid cosy curatorial “themes”, and assemble works to explore a serious problem that is a personal source of worry.

These criticisms have a basis. Parts of the Venice 2005 Italian Pavilion show (curated by Maria de Corral) feel like chocolate-box selections of investment art dusted down from the storerooms of private galleries. Elsewhere in Venice, an independently organised show spotlights both art sponsorship’s capacity to give big bucks and political ambition a smiley face, and the biennale’s capacity to give the enterprise a gloss of glamour and prestige. “First Acquisitions” showcases a handful of flashy, famous-name pieces bought for Kiev’s soon-to-open Contemporary Art Museum by the Foundation for Contemporary Art in Ukraine – creation of Viktor Pinchuk, steel billionaire and son-in-law of the former Ukrainian president Leonid Kuchma. The foundation’s brochure makes friendly noises about fostering “contemporary creation in all different aspects” and Pinchuk’s name leaps off every page. So if you are thinking Pinchuk don’t think corruption, or human misery; think art.

Pinchuk must be aware of the cultural investment made by Michael Bloomberg, mayor of New York. Venice Biennale Live, the broadcast of this year’s alternative big breakfasts, was hosted by Bloomberg and aired by the New York art-radio station WPS1 from a luxurious floating marquee moored near the Giardini.

The agendas for Agendas could not have been more different from Bloomberg’s “salonettes”. Chaired by the critic Sacha Craddock, the salons focused on “fear”, “water”, “risk” and “love” – themes licensing comments from the frivolous to the surprisingly incisive. Leisurely contributions came from John Julius Norwich, Waldemar Januszczak, the international curator Hans Ulrich Obrist and others. Favourite novels were dipped into, jokes cracked and free association indulged, the consensus being that old, academic-style biennale-bothering has hit the buffers. Poetry and repartee are what is needed.

This criticism has some basis, too. However well theorised, conscientious and combative the Agendas style of debate is, it all too often degenerates into an earnest talking shop. Ultimately, biennales operate in political and economic conditions that are way beyond their control; the idea that cultural intervention can make a difference could be a fantasy. Richard Grayson, artist and maverick curator of the Sydney Biennale 2002, has a drastic proposal: a six-year moratorium on biennales and discussions about them. The creation of a big, biennale-shaped hole seems both artistically visionary and theoretically incisive. I say, let’s do it now.

Copyright Rachel Withers & NewStatesman 2005. Information on The Pilots is available here.