Thanks not least to Maud Lavin’s 1993 study, Cut with the Kitchen Knife: The Photomontages of Hannah Hoch, the centrality of Höch’s contribution to Berlin Dada is now generally accepted. But, based on the evidence of Daniel F. Herrmann, Dawn Ades, and Emily Butler’s rewarding Whitechapel Gallery monographic survey, that relationship was a complex one. Their show concluded with an extract from a 1974 German-TV documentary on the artist, in which she introduces her work first as Surrealist and later as an exploration of the “inherent laws of abstract beauty” underpinning artistic form. Neither position sits comfortably with “anti-art” – but then, despite her political commitments, it seems Hoch never really endorsed that Dada war cry. Raoul Hausmann was Höch’s Dada squeeze, but – to judge by the Whitechapel show – Kurt Schwitters, her great friend, was ultimately much stronger aesthetic and imaginative kin. The curators’ selection spanned Höch’s entire career, from the life studies, textile designs, and embroidery patterns of 1912-17 to an extensive selection of late (1945-78) collages. This last body of work in particular refocused one’s view of Hoch, toward the private, the obsessive, the formal, and the poetic: away from Dada and, possibly, toward the land of Merz.

Höch’s incarnation within Dada was represented by pieces such as the collaged Porträt Gerhard Hauptmann, 1919, which splices a smiling female face straight through the Weimar literary lion’s wrinkled mug, or the tiny photograph Weltrevolution (World Revolution), 1920, a reworking of details from Höch’s famous photomontage Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands (Cut with the Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar BeerBelly Cultural Epoch in Germany), 1919. That piece, and several other celebrated Höch Dada montages, were not in the show, but the absences were balanced by a lavish serving of pieces from Höch’s “Ethnographic Museum” series, ca. 1925-30, and contemporaneous, related experiments with collaged human faces and body parts: the disturbing portrait Mischling (Half-Caste), 1924, for example, with its level, unwavering African stare and its absurdly tiny, grafted-on rosebud mouth. At their best, these montaged images are brilliantly concise and arresting – perception in the form of shocks, indeed.

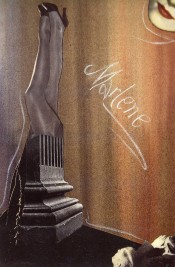

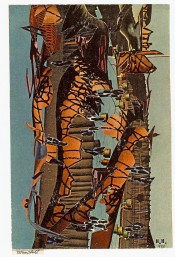

In toto, the exhibition showed that Hoch is best when she is oddest, finding a subtle strangeness, a dépaysement beyond more legible Berlin Dada polemics. Around the show and within its catalogue, much ink has been spilled over her work’s ideological tendencies, and specifically her reuse of photographs of non-Western subjects. In Mischling, for instance, does Hoch enact a Dadaist “performative parody” (in Christopher Townsend’s words) of “objects of political loathing,” or does she simply reiterate the primitivist, exoticizing language of her time and place? It’s a legitimate discussion, no question, but Höch’s radical weirdness slips through its net. Yes, the collage Die Kokette I (The Coquette I), 1923-25, is a satire of the New Woman – but this tiny, solemn, enigmatic heiroglyph is also so much more. When Hoch does polemic and nothing but, by contrast, it’s not as interesting; Take Staatshäupter (Heads of State), 1918-20, for example, or Marlene, 1930, in which two spectators gawp at Dietrich’s legs, inverted on a classical plinth, while the diva’s mouth and chin float, moonlike, in the sky. Sure, the latter work allows great scope for media-studies-style “decoding,” but it’s weak; its slack lines and shaky handwriting, plus the need to cite the actress’s name to render the image legible, all strike a lame note. In Höch’s best pieces, sheer, sneaky oddity trumps the decoding process. Her most polished post-World War II collages are key evidence. Delicate, elusive, intense abstract squiggles with fey, eccentric names – Sumpfgespenst (Swamp Spirit), 1961, or Raumfahrt (Space Travel), 1956, for example – they are both seductive and evasive; one’s eye seems to slither around on their complicated surfaces. Working in her Berlin suburb after the war, alone but for the Schwitters-esque cabinet of artistic relics she’d saved from destruction, Hoch chose to speak a language much closer to Merz than to Dada.

Text © Rachel Withers and Artforum International, 2014

Images © Hannah Höch / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Germany